New research uncovers how tumours use TGF-β to build a powerful double barrier against the immune system and how it might be dismantled (Figure 1).

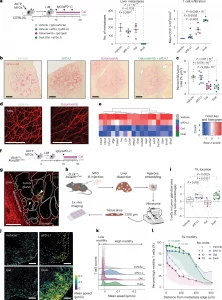

Figure 1: Inhibition of T cell motility by PD-1–PD-L1 interactions but not by TGF-β signaling. a, Therapeutic interventions were initiated on day 15 after intrasplenic (IS) injection of AKTP MTOs to establish liver metastases (LiMs) in C57BL/6J mice (Tx, treatment 15 d). Quantification of liver metastasis number (left) and CD3+ T cell densities (cells per mm2) assessed by immunohistochemistry (right). Mice per group: vehicle (Veh), n = 4; anti-(α)PD-L1 therapy, n = 5; galunisertib (Gal), n = 4; dual therapy, n = 5. Mean ± s.e.m. b,c, Collagen deposition in liver metastases after 3 d of treatment was evaluated by Picrosirius red staining. b,c, Representative images (b) and quantification per area (c). Mice per group: vehicle, n = 9; anti-PD-L1 therapy, n = 8; galunisertib, n = 9; dual therapy, n = 8. Mean ± s.e.m. SR, Sirius red. d, Representative SHG imaging of collagen fibers in liver metastases, shown as a maximum intensity projection of a 100-μm z stack (1-μm intervals). Experiments included at least three animals and were independently replicated three times. Scale bars, 100 µm. e, Bulk RNA-seq analysis of ECM-related gene expression in metastases after 3 d of treatment (n = 3 mice per group). f, Schematic of acute in vivo treatment (3 d) in dLckCre;Rosa26mTmG mice bearing liver metastases. g, Representative ex vivo fluorescence image of a fresh liver metastasis section. mTomato (red) labels all liver and stromal cells; mGFP (green) marks T cells, where mGFP denotes membrane-targeted green fluorescent protein. Tumor glands indicated by solid lines lack fluorescence; metastasis edges are indicated by dashed lines. T cells localize to the stroma (arrowhead) or within tumor glands (triangle). Scale bar, 200 μm. h, Workflow schematic for ex vivo intratumoral T cell motility imaging. Fresh liver slices embedded in low-melting point agarose were sectioned (200 μm) and cultured in μ-Slide 8 Well chambers with Advanced DMEM/F12 medium (see the Methods for details). i, log ratio of T cells in tumor glands versus stroma per metastasis and per mouse. Large dots represent mouse averages; small dots represent individual metastases. Mice per group: vehicle (six mice, 38 metastases), anti-PD-L1 therapy (five mice, 34 metastases), galunisertib (three mice, 26 metastases), dual therapy (eight mice, 35 metastases). j, Representative T cell motility tracks from ex vivo imaging over 20 min. Color scale indicates mean speed (μm s−1). Scale bar, 200 μm. k, Distribution of T cell mean speed (μm s−1) for each treatment. Cell motility was classified as low or high based on thresholds derived from the average speed and the 95th percentile observed for all vehicle-treated cells (see the Methods for details). l, Percentage of high-motility T cells at incremental distances from the metastasis edge (0.01-μm steps) toward the tumor core. Dot size reflects the number of metastases (mets) analyzed at each distance (same n values as in those in i). Mean ± s.d. For every distance (anti-PD-L1 therapy, galunisertib and dual therapy), cell activity was compared to that of the vehicle group by fitting a mixed linear model. Statistical significance (P ≤ 0.05) indicates the closest distance from the edge with a treatment effect compared to the vehicle, determined by mixed linear models. Box plots display median and interquartile range, and whiskers extend to minimum and maximum values. All statistical tests were two sided and corrected for multiple comparisons when applicable. Statistical analyses included a generalized linear model with a negative binomial family (a, metastasis number), a linear model with log transformation (a, CD3+ quantification), a linear model with experiment as the covariate (c) and a linear mixed-effect model with Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test (i). Arrowheads indicate T cells. Panels a, f and h were generated with BioRender.com.

Colorectal cancer remains one of the leading causes of cancer-related death worldwide. While immunotherapies have revolutionized treatment for several cancers, most patients with metastatic colorectal cancer do not benefit from these approaches. A new study explains why and points toward strategies that could make immunotherapy work for more patients.

The study reveals that colorectal tumours exploit a signalling molecule called TGF-β (transforming growth factor beta) to create a two-layer defence that blocks immune attack.

The immune system relies heavily on T lymphocytes (T cells) to recognize and kill cancer cells. The researchers discovered that TGF-β protects tumours by acting on two fronts:

- Blocking immune entry

TGF-β prevents enough tumour-fighting T cells from exiting the bloodstream and entering metastatic tumours. - Suppressing immune expansion inside tumours

For the few T cells that manage to infiltrate the tumour, TGF-β reprograms macrophages to produce osteopontin, a protein that slows T-cell proliferation and dampens their activity.

Together, these mechanisms render the tumour largely invisible to the immune system.

To uncover these mechanisms, the team combined mouse models of metastatic disease with analyses of patient tumour samples, applying advanced single-cell sequencing technologies.

When the researchers blocked TGF-β signalling in experimental models, immune cells flooded into tumours and regained their ability to attack cancer cells. Importantly, combining TGF-β blockade with immunotherapy produced strong anti-tumour responses, far exceeding either approach alone.

While drugs that inhibit TGF-β already exist, their clinical use has been limited due to side effects. This study suggests alternative strategies, such as targeting downstream effects of TGF-β, including osteopontin production, may offer a safer way to restore immune activity when used alongside immunotherapy.

By decoding how colorectal tumours actively repel and suppress immune cells, this research provides a clear roadmap for improving immunotherapy effectiveness. Rather than stimulating the immune system alone, future treatments may need to first dismantle the tumour’s defensive microenvironment.

Journal article: Henriques, A., et al. 2025. TGF-β builds a dual immune barrier in colorectal cancer by impairing T cell recruitment and instructing immunosuppressive SPP1+ macrophages. Nature Genetics.

Summary by Stefan Botha