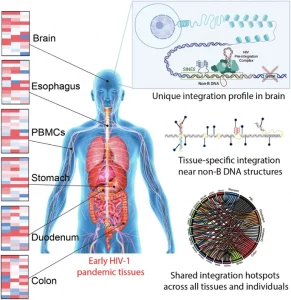

A new study from researchers has uncovered how HIV hides in different parts of the body by integrating into the DNA of infected cells in a tissue-specific manner (Figure 1). The findings reveal that the virus exploits unique DNA patterns in each organ, helping explain why it persists for decades despite effective treatment.

The team discovered that HIV does not embed itself randomly within the genome. Instead, it follows distinct integration patterns shaped by the local environment and immune activity. For example, in the brain, HIV tends to insert into less active regions of DNA, avoiding highly expressed genes, effectively concealing itself from immune surveillance and antiviral drugs.

The study drew on rare, historic tissue samples from individuals infected during the early HIV/AIDS epidemic (circa 1993), before modern antiretroviral therapy existed. This allowed the researchers to examine how the virus naturally distributed across multiple organs, including the blood, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and colon, within the same individuals. The integration patterns were then compared across tissues, revealing profound regional differences in how HIV embeds and persists.

By mapping these genomic “hiding spots,” the researchers aim to guide future therapies that can either eliminate infected cells or silence the virus where it lies dormant.

The study also stands as a tribute to the patients who contributed samples during the uncertain early years of the HIV epidemic, a legacy of courage and scientific foresight that continues to advance the fight against the virus today.

Journal article: Kohio, H. P., et al. 2025. Early pandemic HIV-1 integration site preferences differ across anatomical sites. Communications Medicine.

Summary by Stefan Botha