- Patient presentation

- History

- Differential Diagnosis

- Examination

- Investigation

- Discussion

- Final Outcome

- ARV Treatment Guidelines in RSA

- References

- Evaluation - Questions & answers

- MCQ

Patient presentation

A 17 year old male presents to the hospital emergency room with a one week history of headache, fever, sore throat, painful swellings in the neck and muscle aches. He recently travelled to Mozambique and is requesting a malaria test.

History

Mr L. travelled to Mozambique, one month ago (high risk season), with his parents. He took no malaria prophylaxis but took necessary precautions in the evening. He does not recall being bitten.

Mr. L is a 17 year old male who lives in a community outside of Johannesburg. He shares a 3 roomed house with his parents and two younger brothers. They have electricity and running water. Both parents are employed and Mr. L is in his final year of high school.

One week ago:

He attended his local clinic with a headache and fever and was diagnosed with influenza. He was booked off school for 3 days and given amoxicillin 500mg pd. However, his symptoms have worsened over the past week.

Past medical and surgical history:

- His health throughout his childhood has been uneventful, with chickenpox at age 7 and two episodes of tonsillitis at age 5 and 12. He made a full recovery after each event.

- He has been fully vaccinated.

- He is not on any chronic medication and has no known allergies.

- He has had no previous surgery.

Family and Social history:

- Currently there is no one else ill at home.

- Mr. L has a smoking history of 1 pack per year.

- He consumes some alcohol (mostly beer) at the weekends, occasionally getting intoxicated (but cannot quantify).

- No recreational drug use.

- He does not have a girlfriend but has been sexually active with 5 different female partners in the last year. He occasionally uses condoms. His last sexual encounter was 3 weeks ago.

Differential Diagnosis

- Influenza

- Glandular Fever

- Pharyngitis

- Acute retroviral syndrome

- Malaria

Examination

Vitals:

- BP: 105/55

- Temp: 39 degrees-C

- Respiratory rate: 24

- Pulse: 100

General:

- Tender cervical and axillary lymph nodes

- No pallor

- No jaundice

ENT:

- Erythematous pharynx, no exudate

Skin:

- Fine maculopapular rash on face and trunk

- The rest of the examination was nil of note.

Investigation

| Urine Dipstick | ||

|---|---|---|

| Leukocyte Esterase | Negative | |

| Glucose | Negative | |

| Protein | Negative | |

| Ketones | Negative | |

| Blood | Negative | |

| FBC: | ||

| WCC | 3.0 x 10ˆ9/l | (4.00 – 10.00), atypical lymphocytes seen on diff |

| Hb | 13.0 g/dl | (12.1 – 15.1 g/dl) |

| Platelets | 100 x 10ˆ9/l | (150 – 400) |

| Urea Creatinine and Electrolytes | ||

| Na | 138 | (135 – 147 mmol/l) |

| K | 4 | (3.3 – 5.0 mmol/l) |

| Cl | 100 | (99 – 103 umol/l) |

| HC03 | 18 | (18 – 29 mmol/l) |

| Urea | 5.2 | (2.5 – 6.4 mmol/l) |

| Creatinine | 98 | (62 – 115 mmol/l) |

| Paul Bunnell (for infectious mononucleosis) | Negative | |

| Malaria Smear | Negative | |

| Throat Swab | No pathogenic bacteria isolated | |

| Alere™ HIV Combo – Rapid Test | Postive | Alere HIV Combo – Rapid Test |

| 4th Generation HIV ELISA | Positive | p24 antigen |

An Alere™ HIV Combo – Rapid Test was conducted which was positive for p24 antigen (Ag). A 4th generation ELISA test was also performed and this confirmed the Alere HIV Combo – Rapid Test results.

Discussion

On presentation of Mr L at the clinic, there was very little offered in terms of making a diagnosis. Clinically he presented with four signs of an inflammatory response- fever, pharyngitis, lymphadenopathy and rash. The Alere HIV Combo – Rapid Test was positive for p24 antigen. A 4th generation ELISA test was also performed and this confirmed the Alere HIV Combo – Rapid Test results. It was concluded that he was acutely infected with HIV and was showing signs of acute retroviral syndrome.

Fever or elevation of body temperature is caused mainly by TNF-alpha, IL-1 and IL-6. These are termed endogenous pyrogens. These cytokines are a part of the innate immune system and cause the increase in the thermoregulatory set-point in the hypothalamus. Fever is generally beneficial because pathogens grow better at lower temperatures and adaptive immune responses are more intense at elevated temperatures. In this case, the initial inflammatory cytokine cascade allowed HIV to replicate, promoting the development of a HIV reservoir.

Stages of HIV Infection

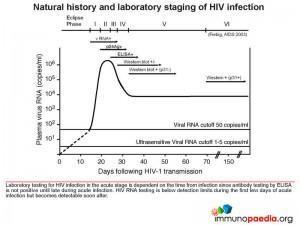

Let’s look at the different stages of HIV diagnosis in more detail. Figure 1 shows Fiebig staging of laboratory testing for HIV infection. Fiebig staging is a 6-stage classification system that was formulated for staging early HIV infection based on the different times viral markers and host antibody responses emerge. The system was named after the paper’s first author). It is likely that Mr L was in the the acute stage (Fiebig I/II), prior to seroconversion and when there is peak viraemia. It is known at this stage, there is a cytokine storm – where proinflammatory cytokine levels are high, giving rise to the fever, pharyngitis, lymphadenopathy and rash. As the peak viral load equilibrates to a set point, the Alere HIV Combo – Rapid Test and ELISA test show the presence of anti-p24 antibodies and the production of large amounts of viral proteins.

The Alere HIV Combo – Rapid Test can detect free p24 antigens in the Ag line, however it cannot detect antibody-p24-antigen complexes. The test also detects HIV-1 and HIV-2 antibodies in the Ab line, both free and immune-complexed.

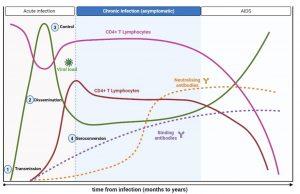

Figure 2 Typical immune response to HIV. A typical immune response to untreated HIV infection shows a rapid increase in viraemia in the early acute phase which declines to a set point. A decline in CD4+ T cells coincides with the increase in viral load. HIV-specific CD8+ Cytotoxic T cell responses reduces the viral load and an increase in CD4+ T cells is seen. HIV-specific binding antibodies appear after the reduction of viraemia, but antibodies are detectable by ELISA only later in acute infection. During chronic infection, CD4+ T cells decline slowly and viral load remains stable. Neutralizing antibodies begin to appear. Continued HIV replication and immune evasion exhausts the immune system leading to opportunistic infection and AIDS. Created in https://BioRender.com (CA Petersen 2024)

The Immune Response to HIV

There appears to be an ordered series of events that occur upon HIV acquisition. Figure 2 shows a typical immune response to untreated HIV infection. After transmission of HIV to a new host (1), there is dissemination of the virus to lymphoid tissues (2) and a rapid increase in viraemia in the acute phase (measured as Fiebig stage I). The fall in peak viraemia is thought to be due to the initial immune control (3) and viral load declines to a setpoint. A decline in CD4+ T cells coincides with the increase in viral load. HIV-specific CD8+ Cytotoxic T cell responses are thought to reduce systemic viral load and an increase in CD4+ T cells is often observed. HIV-specific binding antibodies appear after the reduction of viraemia (4, Fiebig stage III onwards). During chronic infection, CD4+ T cells decline slowly and viral load remains relatively stable. Neutralising antibodies begin to appear only after about 9 months and continued HIV replication and immune evasion exhausts the immune system leading to opportunistic infection and AIDS.

Let’s look at each of these four stages in closer detail:

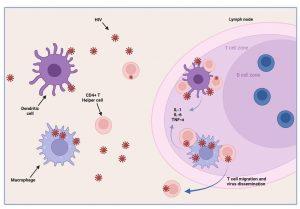

1) HIV Transmission

Infection is a “rare” event. In 80% of cases, transmission infection is established by a single virus particle. All micro organisms that penetrate the epithelial surfaces are met immediately by cells and molecules that can mount an innate immune response. Epidermal Langerhans’ cells are a subset of dendritic cells found in the squamous epithelium of the female vagina and male inner foreskin and are the first immune cells to contact HIV during heterosexual contact. They express surface CD207 (langerin) that captures virus by binding to gp120, which induces internalisation and degradation of virus particles. Activated Langerhans’ cells migrate to draining lymph nodes for antigen presentation to CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. In the process, CD4+ T cells can also become infected by virus bound to the Langerhans cell surface (trans-infection). Langerhans’ cells may also express CD4 and CCR5 and can become infected themselves. Activated Langerhans’ cells produce pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-alpha that, as discussed, can cause fever. Dilation and increased permeability of the blood vessels during inflammation leads to increased local blood flow and the leakage of fluid, and accounts for the heat, redness and swelling (pharyngitis) observed in Mr L’s acute retroviral syndrome.

Figure 3 HIV transmission. Epidermal Langerhans cells are a subset of dendritic cells found in the squamous epithelium of female vagina and male inner foreskin, and are the first immune cells to make contact with HIV during sexual interaction. They express surface CD207 (langerin) that capture virus by binding to gp120 which induces internalisation and degradation of viruses. Activated cells migrate to draining lymph nodes for antigen presentation to CD4+ T cells which can also become infected by surface bound virus. Langerhans cells also express CD4 and CCR5 and can become infected themselves. Activated Langerhans cells produce pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-α that can cause fever in acute infection. Created in https://BioRender.com (CA Petersen 2024)

2) HIV Dissemination

Afferent lymphatic vessels drain fluid from the tissues and carry antigen bearing cells from infected tissues to the lymph nodes where they are trapped. Follicles expand as B lymphocytes proliferate to form germinal centres and the entire lymph node enlarges. This would explain the clinical observation of lymphadenopathy. HIV infected CD4+ T cells, activated in genital draining lymph nodes, migrate to mucosal tissues such as the gut and skin. Dissemination of virus results in increased viral replication, mainly in lymph organs and leads to high viral loads in peripheral blood. There is also a rapid depletion of CD4+ T helper cells, particularly in the gut lymphoid tissues. Tissue macrophages express CD4 and CCR5 receptors and also become infected. Dendritic cells are CD4 negative but can capture HIV on surface CD209 (DC-SIGN) molecules and mediate trans-infection of CCR5-bearing CD4+ T cells. Cutaneous immune responses to HIV are thought to cause the maculopapular rash observed in Mr L, involving primarily the face and trunk. Localised anti-HIV skin responses have been shown experimentally in the macaque-SIV model. Although less common, hives and pruritic papules and pustules can occur on the extremities. A skin biopsy of the rash shows features similar to other viral exanthems and morbilliform drug eruptions. Most commonly, the dermis contains a superficial perivascular CD4+ lymphocytic infiltrate and the epidermis shows spongiosis with individual necrotic keratinocytes. The exact mechanism of how the rash forms remains poorly understood but is thought to be caused by homing of HIV-infected CD4+ T cells (expressing alphaEBeta7 integrin) to the skin that precipitates a local inflammatory response.

Figure 4 HIV dissemination. Infected CD4+ T lymphocytes activated in the genital draining lymph nodes migrate to the other tissues such as the gut and mucosa associated lymphoid tissue and the skin. Dissemination of the virus results in increased viral replication, mainly in lymph organs and leads to high viral loads in the peripheral blood. There is also rapid depletion of CD4+ T helper lymphocytes, particularly in the gut. Cutaneous immune responses to HIV are thought to cause maculopapular rash seen in acute infection. Tissue macrophages express CD4 and CCR5 receptors and also become infected. Dendritic cells are CD4- but can capture HIV on surface CD209 (DC-SIGN) molecules and also mediate infection of CD4+ T lymphocytes. Created in https://BioRender.com (CA Petersen)

3) Control of Viraemia

The partial resolution of peak viral load observed during the acute stage of HIV infection is associated with robust T cell immunity. Tissue dendritic cells engulf virus detected in extracellular spaces and present viral peptides by both HLA class I and II molecules in the lymph nodes to CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, respectively. Activated HIV-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes impart viral control by killing HIV infected cells and reducing viral replication. This response is not sufficient to eradicate the virus, but reduces viral load and allows CD4+ T helper lymphocyte numbers to increase. The absolute CD4+count does not however return to baseline levels but remains reduced.

Figure 5 Control of viraemia. Tissue dendritic cells engulf virus detected in extracellular spaces and present viral peptides in association with HLA class I and II receptors to T cells in the lymph node. Activation of HIV-specific CD4+ Helper T lymphocytes and CD8+ Cytotoxic T lymphocytes leads to reduced viral replication due to the cell-killing action of CD8+ Cytotoxic T lymphocytes. This response is not sufficient to eradicate the virus, but reduces viral load and allows CD4+ T helper lymphocyte numbers to increase. CD4+ count does not however return to baseline levels but remains reduced.

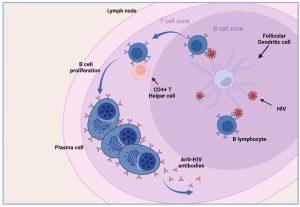

4) Seroconversion

As can be appreciated from the preceding discussion, there has been a multitude of immunological events occurring prior to seroconversion, many of them resulting in the clinical symptoms of acute retroviral syndrome. Antibodies to HIV (seroconversion) only begin to appear in peripheral blood 4-6 weeks after transmission, but in rare instances can take up to 3 months. In order for HIV-specific antibodies to be generated there must be sufficient presentation of HIV antigens to B lymphocytes. This is achieved by capture of viral particles and proteins on the surface of follicular dendritic cells located in the lymphoid follicles (B cell zone) of the lymph node. In addition, HIV-specific CD4+ helper T cells are required to provide activation signals for B cells to differentiate into plasma cells.

Figure 6 Seroconversion. Antibodies against HIV begin to appear in the peripheral blood a few weeks after infection (seroconversion). In order for HIV specific antibodies to be generated there must be sufficient presentation of HIV antigens to B lymphocytes. This is done by capture of viral particles and protein on the surface of follicular dendritic cells located in the germinal centre (B cell zone) of the lymph node. In addition, HIV-specific CD4+ helper T lymphocytes are required to provide activation signals for B lymphocytes to differentiate into plasma cells. Created in https://BioRender.com (CA Petersen 2024)

Final Outcome

Based on the patient’s risky sexual practices he was offered voluntary counselling and testing (VCT). Blood was taken and a fourth generation HIV ELISA was used to detect p24 antigen. This confirmed the positive for p24 antigen (Ag) result from the fourth generation Alere HIV Combo – Rapid Test.

Older, 3rd generation rapid tests are of limited value during primary HIV infection as they do not detect p24 antigen, they only detect HIV antibodies and specific HIV antibodies only become detectable in the blood towards the end of the symptomatic phase of the illness. While due to the high initial viraemia, viral p24 antigen is invariably present during the symptomatic stage of primary HIV infection and can be used to diagnose infection at this stage. The Alere HIV Combo – Rapid Test is able to detect free p24 antigens and the test results are available in 20 – 40 minutes.

During primary infection and the weeks following this period, the patient is highly infectious and must be advised to practice safe sex or abstain.

Mr L was referred to an ARV clinic for counselling. Based on the ARV Treatment Guidelines in South Africa, the following assessments were performed where appropriate.

Baseline and routine clinical and laboratory assessments after positive HIV diagnosis.

| Baseline and routine clinical and laboratory assessment for late adolescents and adults | |

|---|---|

| CD4 count | All HIV positive patients offered ART |

| ART prioritisation at CD4 ≤350/μl | |

| ART fast-tracking at CD4 ≤200/μl | |

| Determine need to initiate Opportunistic Infection prophylaxis at CD4 ≤200 | |

| Eligibility for CrAg or CLAT at CD4 ≤100/μl | |

| Screen for pregnancy or ask if planning to conceive | To identify women who need ART for PMTCT and offer appropriate family planning |

| Assessment of hypertension and diabetes with blood pressure and urine glycosuria | To identify any concomitant chronic diseases |

| Screen for TB symptoms using the TB screening tool | To identify those with TB symptoms and to assess eligibility for INH |

| Screen for HBV (HBsAg) | To identify those co-infected with HBV so that they can be initiated on ART regardless of CD4 count |

| Screening for STIs and syphilis | To identify and treat STIs |

| Cryptococcus Antigen (CrAg) test if CD4 ≤100 cells/μl | To assess if there is disseminated Cryptococcal infection and if fluconazole treatment is indicated |

| Do Hb or FBC if requires AZT | To detect anaemia or neutropenia |

| Creatinine if requires TDF | To assess renal sufficiency |

| ALT if requires NVP | To exclude liver dysfunction |

| Fasting cholesterol and triglycerides if requires LPV/r | To identify at risk of LPV/r related hyperlipidaemia. If above 6 mmol/L, consider (ATV/r) instead of LPV/r (if available) |

In addition, a baseline HIV viral load should be performed where feasible.

TDF can only be used in patients with Creatinine clearance >50 mL/min and creatinine <100 μmol/L. Other NRTIs, except abacavir (ABC), require dose adjustment if creatinine clearance is <50 ml/min.

2023 ARV Treatment Guidelines in RSA

2023 Guidelines in South Africa for Starting Antiretroviral (ARV) Treatment

South Africa is among the first countries in Africa to formally adopt Universal Test and Treat (UTT) in accordance with the WHO new guidelines on HIV treatment. UTT directly supports UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets of ensuring that 90% of all people living with HIV know their HIV status, 90% of people with diagnosed HIV infection receive sustained ART and 90% of all people receiving ART have viral suppression. South Africa embraces UTT to complement case finding and holding strategies that are reflected in the revised 2023 National HIV Testing Services (HTS) Policy and the 2016 HIV Disclosure guidelines. Key to success of Universal Test and Treat is implementation of the National Adherence Policy and service delivery guidelines interventions for linkage to care, adherence to treatment and retention in care.

Eligibility Criteria for Universal Test and Treat (UTT)

With effect from 1st June 2023 the following criteria to start patients on lifelong ART applies:

- All people living with HIV (PLHIV) are eligible to start ART regardless of age, CD4 count and clinical stage.

- For patients without contra-indications, ART should be initiated within 7 days or on the same day if possible.

- Pregnant women, infants and children under five years, and patients with advanced HIV disease should be prioritized for rapid initiation.

- Patients may access ART on the same day as HIV diagnosis, provided that they are clinically well and motivated to start ART.

- While rapid, and same day AR initiation is encouraged where possible, all patients, particularly those with advanced HIV disease, should be carefully assessed for opportunistic infections (OIs) that may necessitate ART deferral.

Timing of ART initiation

ART should be started as soon as the patient is ready and within 2 weeks of CD4 count being done. Immediate priority is given to all HIV-positive pregnant or breastfeeding women, with no active TB or contradiction to FDC (TDF/FTC/EFV). Fast track initiation is given to HIV stage 4 patients with CD4 ≤200 cells.

Initial ART Regimens for the Previously Untreated Patient

| Indication | Action |

|---|---|

| TB symptoms (cough, night sweats, fever, recent weight loss) | Investigate symptomatic clients for TB before initiating ART. If TB is excluded, proceed with ART initiation and TB preventive therapy (after excluding contraindications to TPT). If TB is diagnosed, initiate TB treatment and defer ART. The timing of ART initiation will be determined by the site of TB infection and the client’s CD4 cell count |

| Diagnosis of drug-sensitive (DS) TB at a non-neurological site (e.g. pulmonary TB, abdominal TB, or TB lymphadenitis) | Defer ART initiation as follows: |

| · If CD4 | |

| · If CD4 ≥ 50 cells/μL – initiate ART 8 weeks after starting TB treatment | |

| · In pregnant and breastfeeding women (PBFW) initiate ART within 2 weeks of starting TB treatment, when the client’s symptoms are improving, and TB treatment is tolerated. Defer ART for 4-6 weeks if symptoms of meningitis are present. For further details, refer to the Family-Centred Transmission Prevention Guideline 2023 | |

| Diagnosis of drug-resistant (DR) TB at a non-neurological site (e.g. pulmonary TB, abdominal TB, or TB lymphadenitis) | Initiate ART after 2 weeks of TB treatment, when the client’s symptoms are improving, and TB treatment is tolerated |

| Diagnosis of DS-TB or DR-TB at a neurological site (e.g. TB meningitis or tuberculoma) | Defer ART until 4-8 weeks after start of TB treatment |

| Signs and symptoms of meningitis | Investigate for meningitis before starting ART |

| Cryptococcal antigen (CrAg) positive in the absence of symptoms or signs of meningitis and if lumbar puncture is (LP) negative for cryptococcal meningitis (CM) | No need to delay ART. ART can be started immediately |

| Confirmed cryptococcal meningitis | Defer ART until 4-6 weeks of antifungal treatment has been completed |

| Other acute illnesses e.g. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PJP) or bacterial pneumonia | Defer ART for 1-2 weeks after commencing treatment for the infection |

| Clinical symptoms or signs of liver disease | Confirm liver injury using ALT and total bilirubin levels. ALT elevations > 120 IU/L with symptoms of hepatitis, and/or total serum bilirubin concentrations > 40 µmol/L are significant. Investigate and manage possible causes including TB, hepatitis B, drug-induced liver injury (DILI), or alcohol abuse |

| Note: Clients who are already on ART should NOT have their treatment interrupted upon diagnosis of the above conditions | |

Timing of ART initiation

When MR L was diagnosed with HIV he was treated according to the 2016 ART guidelines for management, furthermore this case study will discuss treatment according to the updated 2023 treatment guidelines specifically for Mr L’s case.

A clinical assessment and laboratory baseline investigations should be done in order to initiate ART. However, laboratory results do not need to be available to start patients on ART on the same day, provided they have no clinical evidence of TB, meningitis or renal disease. In addition, all patients, and caregivers of paediatric clients, must receive counselling on how to administer medication, monitor side-effects and deal with challenges to adherence.

The following baseline laboratory investigations should be performed routinely before a patient initiates ART. Patients are not required to wait for the results of the baseline investigations prior to starting ART, but results should be checked at the next visit.

| Baseline and routine clinical and laboratory assessment for late adolescents and adults | ||

|---|---|---|

| Laboratory evaluation | Purpose | Adolescents (10-19 years) and Adults |

| Confirm HIV test result | To confirm HIV status for those without documented HIV status | Ö |

| CD4 count | To identify eligibility for CPT | CD4 count ≤ 200 cells/μL, WHO Stage 2, 3 and 4 |

| To identify eligibility for cryptococcal antigen (CrAg) screening | A reflex CrAg test will be done automatically by the laboratory on all CD4 counts | |

| Creatinine and eGFR if TDF used | To assess renal insufficiency | Acceptable level for TDF use |

| eGFR using MDRD equation1 (>16 years): | ||

| · >50 mL/min/1.73m2 | ||

| eGFR using Counahan Barratt formula (≥10 and | ||

| · > 80 mL/min/1.73 m2 | ||

| Haemoglobin (Hb) | To identify and manage anaemia; to determine eligibility for zidovudine (AZT) where necessary | If Hb is low, do a full blood count (FBC). Characterise according to mean corpuscular volume (MCV) as either microcytic, normocytic, or macrocytic and manage accordingly |

| GeneXpert (MTB/Rif Ultra) | To diagnose TB | For any patient with a positive TB symptom screen |

| For people living with HIV, regardless of TB symptoms: | ||

| • At the time of HIV diagnosis | ||

| • On enrolment in antenatal care for pregnant women | ||

| Cryptococcal antigen test (CrAg) if CD4 | To identify asymptomatic clients who need pre-emptive fluconazole treatment | A reflex CrAg test will be done automatically by the laboratory on all CD4 counts |

| ART regardless of CD4 count | ||

| Cervical cancer screening | To identify women with cervical lesions and manage appropriately | All HIV-positive women should be screened for cervical cancer at diagnosis and subsequently every 3 years if the screening test is negative. If the cervical screening results suggest a possible abnormality of the cervical cells, then a clear plan for further investigation and treatment (e.g. colposcopy and LLETZ procedure) should be determined according to the local referral guidelines. |

| HBsAg | To identify those co-infected with hepatitis B (HBV) | If positive, exercise caution in stopping TDF-containing regimens, to prevent hepatitis flares |

Initial ART Regimens for the Previously Untreated Patient

| ART regimens for adolescent and adults, including pregnant and breastfeeding women | ||

|---|---|---|

| POPULATION | DRUG | COMMENTS |

| All adult and adolescent males and females, including pregnant women ≥ 30kg and ≥ 10 years of age | TDF + 3TC + DTG provide as fixed-dose combination (FDC) | Consider simultaneously initiating TB preventive therapy if patient shows no signs of active TB |

| Adult or adolescent ≥ 15 years (non-pregnant) -TB preventative therapy | Isoniazid, oral, 300 mg daily for 12 months (12H) and pyridoxine 25 mg daily Rifapentine and isoniazid weekly (3HP) may be available in selected locations* | Any CD4 count. Exclude active liver disease, alcohol abuse, or known hypersensitivity to isoniazid |

| Adults and adolescents on EFV (or NVP) | Change EFV to TDF (DTG regimen) | Switch all to DTG-containing regimen, regardless of VL |

| Provided no renal dysfunction and age ≥ 10 years and weight ≥ 30 kg | ||

| CONSIDERATIONS | SUBSTITUTION DRUG | COMMENTS |

| Patient with active TB (rifampicin containing TB treatment) | If on TDF or ALD, add DTG 50mg 12 hourly after TLD dose | due to significant drug interaction of rifampicin and DTG, a boost dose is required |

| Continue boosting the ART regimen until 2 weeks after stopping rifampicin | ||

In accordance with international recommendations, the guidelines recommend the use of a reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) and 2NRTIs (a safe dual NRTI combination) as the first-line ART regimen. In comparison with PIs, NNRTIs are better tolerated in the long-term and are at least as potent when combined with an appropriate dual NRTI combination. It is not recommended to use PI or an integrase inhibitor in first-line therapy, unless dictated by intolerance or NNRTI contra-indications. According to the 2016 guidelines Efavirenz (EFV) was the preferred NNRTI, however the new updated guidelines (2023) states that Dolutegravir (DTG) is to be used as part of the first line regiment. A literature review conducted by Kanters et al., 2020 , comparing EFV to DTG illustrated that DTG has a high certainty of faster viral suppression, protectiveness with respect to drug-resistance and improved safety, in addition to reduced discontinuation due to adverse effects (DAE). DTG was initially thought to have a high risk for neural tube defects (NTD) during pregnancy and weight gain compared to EFV, however new evidence suggests that there is no risk for NTD and that the weight gain association was not causal, instead the association may be the result of comparatively less metabolic toxicity than alternative older ART regimens (that mitigate weight gain through toxicity) combined with an initial return-to-health phenomenon, and an obesogenic environment (2023 ART Clinical Guidelines for the Management of HIV in Adults, Pregnancy and Breastfeeding, Adolescents, Children, Infants and Neonates | Department of Health Knowledge Hub, n.d.; Nickel et al., 2021).

TDF is the favoured NRTI to use with 3TC or FTC and DTG. Public programmes in South Africa have now slowly started switching patients on EFV ART, to a DTG regiment as first-line ART but EFV can be utilised in particular short-term cases for example when a patient is co-infected with a condition where the treatment may have possible adverse drug interactions with DTG.

Therefore, following the recommended guidelines, Mr L should be initiated on the first line regimen of TDF + 3TC + DTG as a fixed dose combination, along with TB preventative therapy since no signs of active TB was observed, while waiting for his clinical and laboratory results.

References

2023 ART Clinical Guidelines for the Management of HIV in Adults, Pregnancy and Breastfeeding, Adolescents, Children, Infants and Neonates | Department of Health Knowledge Hub. (n.d.). Retrieved December 4, 2024.

Kanters, S., Vitoria, M., Zoratti, M., Doherty, M., Penazzato, M., Rangaraj, A., Ford, N., Thorlund, K., Anis, P. A. H., Karim, M. E., Mofenson, L., Zash, R., Calmy, A., Kredo, T., & Bansback, N. (2020). Comparative efficacy, tolerability and safety of dolutegravir and efavirenz 400mg among antiretroviral therapies for first-line HIV treatment: A systematic literature review and network meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine, 28, 100573.

Nickel, K., Halfpenny, N. J. A., Snedecor, S. J., & Punekar, Y. S. (2021). Comparative efficacy, safety and durability of dolutegravir relative to common core agents in treatment-naïve patients infected with HIV-1: an update on a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMC Infectious Diseases, 21(1).

NDoH circular: Implementation of the universal Test and Treat strategy for HIV positive patients and differentiated care for stable patients – Southern African HIV Clinicians Society

New Department of Health National Consolidated ART Guidelines – Southern African HIV Clinicians Society

Fiebig EW et al (2003) . Dynamics of HIV viremia and antibody seroconversion in plasma donors: implications for diagnosis and staging of primary HIV infection. AIDS. 2003 Sep 5;17(13):1871-9.

McMichael AJ et al (2010). The immune response during acute HIV-1 infection: clues for vaccine development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010 Jan;10(1):11-23.

Hladik F et al (2008). Setting the stage: host invasion by HIV. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008 Jun;8(6):447-57.

Cohen MS et al (2008). The spread, treatment, and prevention of HIV-1: evolution of a global pandemic. J Clin Invest. 2008 Apr;118(4):1244-54. doi: 10.1172/JCI34706.

Abrahams MR et al (2009). Quantitating the multiplicity of infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C reveals a non-poisson distribution of transmitted variants. J Virol. 2009 Apr;83(8):3556-67

Brenchley JM et al (2006). HIV disease: fallout from a mucosal catastrophe? Nat Immunol. 2006 Mar;7(3):235-9.

Sasseville VG et al (1998). Characterization of the cutaneous exanthem in macaques infected with a Nef gene variant of SIVmac239. J Invest Dermatol. 1998 Jun;110(6):894-901.

Download images for this case

Evaluation – Questions & answers

What is the diagnosis

Approximately 50- 80% of patients who become infected with HIV experience an acute retroviral syndrome 2 to 4 weeks after becoming infected. Patients with this syndrome, all of whom are HIV antibody negative, typically present to primary healthcare providers or primary healthcare clinics. Recognition of acute HIV symptoms therefore requires provider awareness because these patients are at high risk of transmitting infection to sexual contacts.

When is risk of transmission highest?

What is the window period?

What should patients be advised to do during this time?

Multiple Choice Questions

Earn 1 HPCSA or 0.25 SACNASP CPD Points – Online Quiz