- Patient Presentation

- History

- Differential Diagnosis

- Examination

- Investigations

- Discussion

- Treatment

- Final Outcome

- Evaluation - Questions & answers

- MCQs

- References

Patient Presentation

A 7 year old girl presented to her local hospital for the second time in 3 months with arthralgia, a migratory skin rash and fever for 5 days. She was admitted and within 2 days developed a depressed level of consciousness, epistaxis and seizures.

Acknowledgement

This case study was kindly provided by Dr Monika Esser MMed Paed, Head of Division of Immunology, N.H.L.S Coastal Branch, Tygerberg Hospital.

History

Patient was diagnosed one year earlier with pulmonary TB (PTB) on positive cultures obtained from gastric washings. Her PTB infection was accompanied with symptoms of fever and torticollis. She was started on TB treatment but only completed 2 months of treatment.

Six months later she had not resumed TB treatment and was diagnosed with mitral regurgitation on echocardiography, with an elevated antistreptolysin O titre (ASOT) and an elevated anti-dnase test. She was admitted to hospital and treated for acute rheumatic fever (ARF) with benzyl penicillin. The mitral regurgitation normalised on echo and she was discharged.

Over the course of the following 3 months she developed progressive arthritis, progressive loss of joint function and a chronic remitting fever and rash.

Differential Diagnosis

- Post streptococcal arthritis

- Pulmonary TB

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- Acute rheumatic fever

- Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

Examination

An admission child appears miserable and toxic:

- Height and weight < 3rd centile

- Pyrexial – 38°C

- Pale

- Generalised lymphadenopathy

- Urticarial rash

- 2cm hepatosplenomegaly

- Tender and bilaterally limited range of motion in the wrists, knees, ankles and proximal and distal interphalangeal joints of the fingers

2 days later:

- Depressed level of consciousness

- Epistaxis

- Seizures

- Pyrexia ranging from 38-40°C

- Severe hepatosplenomegaly

- Consolidation of right upper lobe of the lung with bronchial breathing

Investigations

Discussion

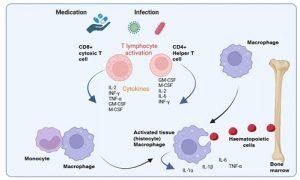

Figure 1 Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) triggered by infection/medication. Although the cause of macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) in patients with rheumatic disorders is unknown, a number of triggers such as viral, bacterial, parasitic or fungal infections as well as certain types of medication have been identified. MAS leads to an intense systemic inflammatory reaction resulting from a dysregulation of lymphocyte and macrophage-derived cytokines (particularly TNF-a, INF-g, IL-1 and IL-6). Increased recruitment and activation of tissue macrophages (histiocytes) in organs and other tissues occurs with abnormal phagocytic activity such as destruction of bone marrow haematopoietic cells. Created in https://BioRender.com (CA Petersen 2025)

Based on the clinical presentation and investigations the differential diagnosis must now include Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS)

- MAS is a form of secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and is most commonly encountered with or associated with underlying rheumatic disorders(Bagri et al., 2021).

- Pal et al., 2020,illustrated that in a single analysis of 31 children diagnosed wit MAS they identified underlying diseases as systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA) in 84%; systemic lupus erythematous (SLE) in 13% and Kawasaki disease (KD) in 3%.

Cause:

- Individuals who are genetically susceptible to developing MAS has a subtle impairment in their cytolytic pathway, that turns into an exaggerated immune response subsequent to a second trigger by either a unknown/self-antigen (as seen in sJIA) or an infectious agent (EBV, bacterial, parasitic and fungal) which seems to be the case for this patient ( pyogenes infections leading to rheumatic fever).

- This potentially leads to an unrestrained activation of immune cells and a hyper-inflammatory state. Excessive activation and proliferation of T lymphocytes and tissue macrophages (histiocytes) with massive cytokinaemia, including high levels of: TNF-a, INF-g, IL-1b, IL-18 and IL-6.

- This produces an overwhelming, potentially fatal, inflammatory reaction. With increased recruitment and activation of tissue macrophages in organs and other tissues with abnormal phagocytic activity such as destruction of bone marrow hematopoeitic cells, liver and spleen cells (Bagri et al., 2021). Clinically, MAS resembles multiorgan dysfunction and shock.

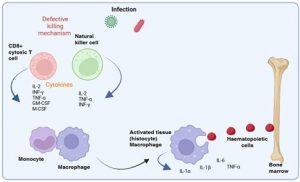

- Defective functioning of perforin (perforin is a protein involved in the cytolytic processes and control of lymphocyte proliferation).

Signs and Symptoms

Figure 2 Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) triggered by immune complex/autoantibodies. Macrophages can also directly be stimulated by immune complexes and autoantibodies. Large quantities of cytokines such as TNF-a, IL-1 and IL-6 are then secreted in response. Created in https://BioRender.com (CA Petersen 2025)

Timely recognition of MAS is of utmost importance and should be considered in any febrile child with underlying rheumatic disease (Cron et al., 2015). The persistent high-grade fever is one of the most important features of MAS, the change in fever from intermittent to non-remitting fever may be an early clue to differentiate MAS from underlying disease flares.

- Non-remitting high fever

- Hepatosplenomegaly

- Lymphadenopathy

- Pancytopenia,

- Liver dysfunction with petechial spots,

- Coagulopathy

- Haemorrhages

- Neurological symptoms

- CNS involvement (drowsiness, headaches and seizures)

Laboratory Features

Figure 3 Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) triggered by defective cytolytic killing. Inherited genetic defects in some of the genes involved in cell killing function, most notably perforin formation, in natural killer cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes can also promote MAS. The failure of these cells to resolve the infection and the ongoing production of cytokines leads to the hyperstimulation of macrophages. Created in https://BioRender.com (CA Petersen 2025)

- Cytopenia

- Abnormal liver function tests

- Coagulopathy Decreased erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- Hypertriglyceridaemia

- Hyponatremia

- Hypoalbuminemia

- Hyperferritinemia

- Histopathological features

- Macrophage hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow (60% of MAS patients)

Epidemiology

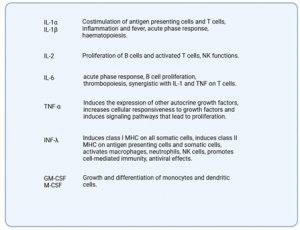

Figure 4 Cytokines involved in macrophage activation syndrome (MAS). Created in https://BioRender.com (CA Petersen 2025)

- Incidence is unknown

- Rare complication

- Most commonly affects children with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA) but has been observed in different subtypes of JIA or in other systemic diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), KD and juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM)

- Generally, develops in the earlier phases of the underlying disease and may occasionally be the presenting manifestation, but occurrence as late as 14 years after diagnosis has been reported

- In most patients, the primary disease is clinically active at the onset of MAS, but the syndrome may also develop during quiescent phases

- Triggered by flare-up of the underlying disease, aspirin or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug toxicity, viral infections, a second injection of gold salts, and sulfasalazine therapy.

Pathogenesis:

The excess production of cytokines (IL-1, IL-6 or IL-8) has demonstrated in in-vitro studies to have an association with NK cell dysfunction, resulting in decreased degranulation i.e., low perforin and granzyme expression:

- Perforin – is a protein that is expressed in lymphocytes, macrophages, and other bone marrow precursors. Its main role in the cytolytic process is to form pores in the cell membrane, leading to osmotic lysis of the target cells.

- May also control lymphocyte proliferation

Diagnostic Guidelines:

According to the 2016 MAS in sJIA classification criteria by Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisations, which has a sensitivity of 73% and specificity of 99% (Cron et al., 2015):

A febrile child with known or suspected sJIA is classified as having MAS if the serum ferritin >684 ng/ml and 2 or more of the following:

- Platelets ≤ 181×109/L

- Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) > 48U/L

- Triglycerides >156 mg/dL

- Fibrinogen ≤360 mg/dL

(b) Variables that did not prove sufficiently sensitive and specific:

- fever (38°C),

- lymphoadenopathy,

- rash

- hemorrhages,

- decreased leukocyte count (below 4,00 x109/L),

- elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (above 50 mm/h),

- elevted lactate dehydrogenase (above 900 IU/mL)

- decreased serum sodium (below 130 mq/L).

Management: Treatment strategies for MAS

MAS is a potentially life-threatening complication. It is therefore important to have a high threshold of suspicion in order to make an early diagnosis and start prompt treatment:

- Parenteral administration of high doses of corticosteroids.

- Cyclosporin A – treating severe or corticosteroid resistant MAS

- It causes a “switch-off” effect on the disease process, leading to resolution of fever and improvement of laboratory abnormalities

- Suppression of the early steps in T-cell activation

- Affects macrophage production of IL-6, IL-1, and TNF

- Inhibits the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthetase and cyclooxygenase-2 in macrophages.

- High-dose intravenous immunoglobulins

- Etanercept might be an effective adjunctive therapeutic agent in MAS.

Diagnostic Rule:

The diagnosis of MAS requires the presence of any 2 or more laboratory criteria or of any 2 or more clinical and/or laboratory criteria. A bone marrow aspirate for the demonstration of hemophagocytosis may be required only in doubtful cases.

Laboratory criteria:

- Decreased platelet count (≤262 x 109/L)

- Elevated levels of AST (> 59 U/L).

- Decreased white blood cell count (≤ 4.0 x 109/L)

- Hypofibrinogenemia (≤2.5 g/L)

Clinical criteria:

- Central nervous system dysfunction (irritability, disorientation, lethargy, headache, seizures, coma).

- Haemorrhages (purpura, easy bruising, mucosal bleeding).

- Hepatomegaly (≥ 3cm below the costal arch)

Histopathological criterion:

Evidence of macrophage hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow aspirate, liver or spleen.

Treatment

- The patient was treated with IVIG and repeated intravenous methylprednisolone pulsing.

Methotrexate was started with normalisation of liver functions. - She required repeat blood transfusions and was kept on broad spectrum antibiotic cover but all cultures remained negative.

Final Outcome

- The patient proceeded to make a rapid and complete recovery and is currently maintained on low dose Methotrexate.

- A full course of TB treatment was completed with normalisation of liver functions.

Evaluation – Questions & answers

What is the diagnosis?

Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) also known as secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis is a macrophage-related disorder of the immune system characterised by excessive activation of tissue macrophages (histiocytes). It is thought that increased levels of lymphocyte and macrophage derived cytokines, particularly TNF-a, INF-g, IL-1, IL-18 and IL-6 lead to the excessive activation of macrophages and systemic inflammation. Increased recruitment and activation of tissue macrophages in organs and other tissues occurs with abnormal phagocytic activity such as destruction of bone marrow haematopoietic cells, liver cells and spleen cells.

What is the cause of Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS)?

The cause is unknown but a number of triggers such as self-antigens in the case of sJIA leading to MAS, infection (in this case seems to be the trigger with S. pyogenes infection) and certain types of medication have been identified.

What is the effect of increased levels of T-cell and macrophage derived cytokines, particularly TNF-a, INF-y, IL-1 and IL-6?

An overwhelming systemic inflammatory reaction, which is potentially fatal.

What is perforin?

Perforin is primarily expressed in CD8+ T cells and NK cells. Its role in the cytolytic process is to form pores in the membrane, leading to osmotic lysis of the target cells. There is evidence that perforin expression is important in preventing both humoral and cellular autoimmunity. Perforin deficient CD8+ and Natural Killer (NK) cells may perpetuate a chronic proinflammatory response. Perforin deficiency may therefore increase macrophage activation due to increased production of IFN-γ and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulator factor (GM-CSF) associated with persistent lymphocyte activation. It is possible that it therefore plays a role in the predisposition to or occurrence of MAS. Most patients with a low perforin expression have had a history of previous MAS episodes.

What is the mechanism of macrophage activation syndrome (MAS)?

Again, this is unclear, however a possible explanation is that patients with MAS have decreased natural killer (NK) function which may be responsible for a diminished ability to kill infected cells and remove the source of antigenic stimulation. This persistent antigen stimulation would lead to persistent antigen driven T-cell activation and proliferation associated with an increased production of cytokines such as IFN-γ and GM-CSF which stimulate macrophages. This sustained macrophage activation causes tissue infiltration with resulting clinical symptoms and tissue damage.

Multiple Choice Questions

Earn 1 HPCSA or 0.25 SACNASP CPD Points – Online Quiz

References

Bagri, N. K., Gupta, L., Sen, E. S., & Ramanan, A. V. (2021). Macrophage Activation Syndrome in Children: Diagnosis and Management. Indian Pediatrics, 58(12), 1155–1161. https://doi.org/10.1007/S13312-021-2399-8

Cron, R. Q., Davi, S., Minoia, F., & Ravelli, A. (2015). Clinical features and correct diagnosis of macrophage activation syndrome. Expert Review of Clinical Immunology, 11(9), 1043–1053. https://doi.org/10.1586/1744666X.2015.1058159

Pal, P., Bathia, J., Giri, P. P., Roy, M., & Nandi, A. (2020). Macrophage activation syndrome in pediatrics: 10 years data from an Indian center. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases, 23(10), 1412–1416. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185X.13915