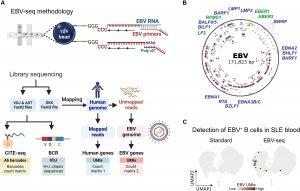

A recent study reveals how Epstein–Barr virus reprograms immune cells to attack the body’s own tissues (Figure 1).

Figure 1: EBV-seq enables identification of EBV-infected B cells. (A) An EBV-seq primer design was incorporated into a 10x Genomics bead-based scRNA-seq workflow that included CITE-seq performed using oligonucleotide-barcoded Abs specific for the prototypical markers for B cell subsets. BCR sequencing was performed by analysis of the expressed variable diversity and joining (VDJ) immunoglobulin genes, followed by analysis of immunoglobulin heavy (H) and light (L) chain gene expression. (B) Shown is the EBV genome annotated with the EBV genes (blue font) and small noncoding RNAs (green font) for which primers were included in EBV-seq. (C) Comparison of standard 10x Genomics scRNA-seq with EBV-seq 10x Genomics scRNA-seq for detection of EBV+ B cells in a PBMC sample from a patient with SLE; EBV UMI counts are represented by intensity of brown dots. ADT, antibody-derived tag.

A virus most people catch as children may hold the key to one of medicine’s enduring mysteries, the cause of lupus, a chronic autoimmune disease that affects tens of thousands worldwide.

The work shows that Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), which usually causes only mild illness, can hijack the immune system and push it into self-destructive overdrive. Lupus occurs when the immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s own tissues, leading to inflammation, fatigue, joint pain, and organ damage. Although genetics and hormones play a role, the underlying trigger has remained unclear, until now.

The team found that EBV infects B cells, the immune cells responsible for producing antibodies. Normally, these cells are tightly controlled to prevent them from reacting to “self” proteins. But in lupus patients, the virus appears to take up residence inside autoreactive B cells, those with the potential to recognize the body’s own tissues, and activates them, setting off a cascade of inflammation.

Using high-precision genetic sequencing, researchers compared immune cells from 11 lupus patients and 10 healthy controls. In healthy individuals, fewer than 1 in 10,000 B cells carried EBV. In contrast, lupus patients had about 1 in 400 infected B cells, a 25-fold increase.

Once activated, these EBV-infected B cells not only attacked the body but also recruited other immune cells, including killer T cells, amplifying the autoimmune response.

The findings could reshape how lupus is diagnosed and treated. If EBV truly drives all or most lupus cases, then preventing EBV infection or eliminating infected cells could stop lupus before it starts. These insights come as clinical trials for EBV vaccines are already under way, raising the possibility of a preventative strategy for lupus and perhaps other autoimmune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, which has also been linked to EBV. Beyond vaccines, researchers are exploring B-cell–targeted therapies, including drugs repurposed from cancer treatments, to selectively remove infected or autoreactive immune cells.

A common childhood virus may be the missing link in lupus. By showing how EBV infects and activates rogue immune cells, this study paves the way for new vaccines and therapies that could finally stop autoimmune disease at its source.

Journal article: Younis, S, et al. 2025. Epstein-Barr virus reprograms autoreactive B cells as antigen-presenting cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. Science Translational Medicine.

Summary by Stefan Botha